Nanostructured Materials for Advanced Energy Storage Systems

The global demand for efficient, high-capacity, and sustainable energy storage solutions has never been greater. In this context, nanostructured materials have emerged as a transformative force, enabling significant advancements in batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells. By engineering materials at the nanoscale (typically 1–100 nanometers), scientists can exploit unique physicochemical properties—such as high surface area, short diffusion pathways, and quantum effects—that are unattainable in bulk counterparts. This article explores the fundamental principles, key material classes, and future prospects of nanostructured materials in energy storage.

Fundamental Advantages of Nanostructuring

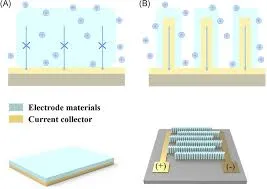

Nanostructuring refers to the design and fabrication of materials with structural features at the nanometer scale. This approach offers several critical benefits for energy storage devices. Firstly, the enormous surface area per unit mass facilitates greater electrode-electrolyte contact, enhancing charge storage capacity and reaction kinetics. Secondly, reduced particle size shortens the path for ion and electron transport, leading to faster charging and discharging rates. Thirdly, nanomaterials can better accommodate volume changes during charge-discharge cycles, improving mechanical stability and cycle life. These attributes collectively address major limitations of conventional energy storage systems.

Key Nanostructured Material Classes and Applications

Various classes of nanostructured materials are being actively researched and deployed for different energy storage technologies.

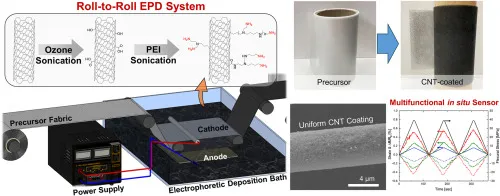

1. Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and porous carbon nanostructures are widely used due to their excellent electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and chemical stability. Graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms, is particularly notable for its ultra-high surface area (≈2630 m²/g) and conductivity. It serves as an ideal conductive additive or active material in supercapacitors and lithium-ion battery anodes.

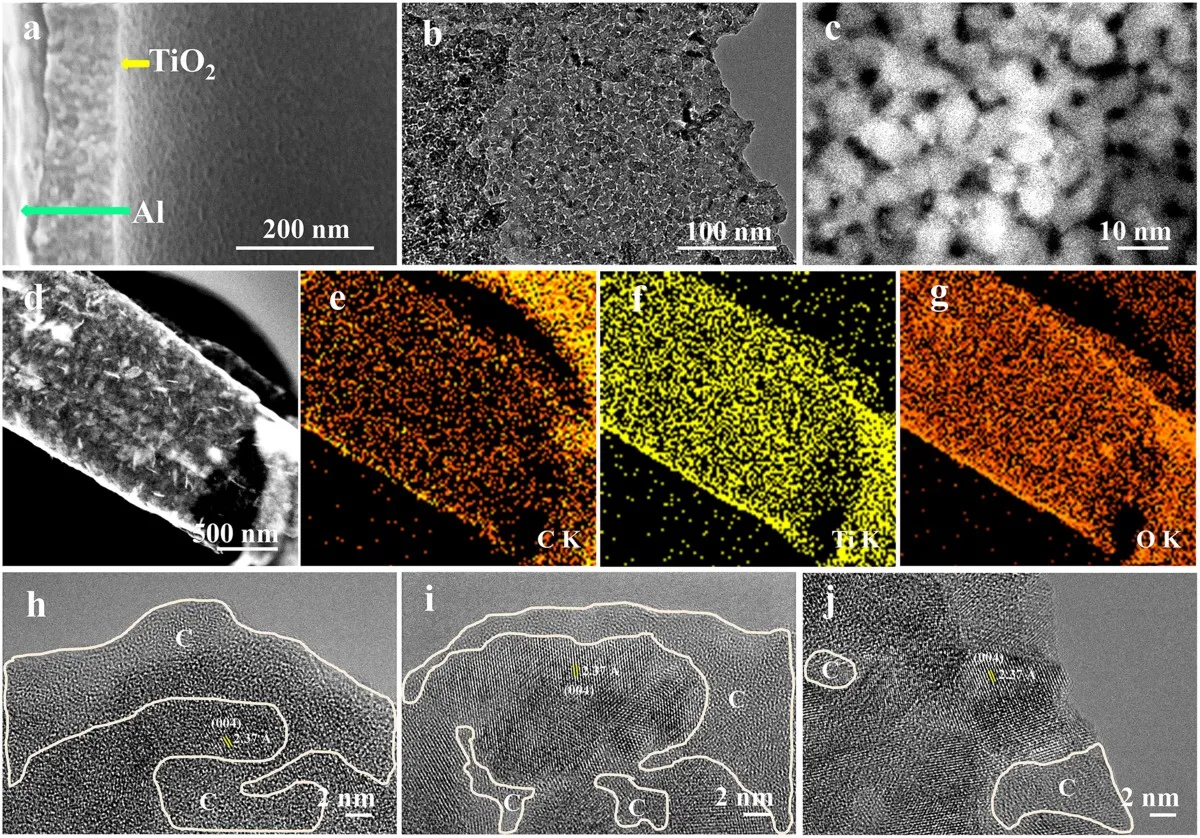

2. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles and Nanowires

Transition metal oxides (e.g., TiO₂, MnO₂, Fe₃O₄) in nanoparticle or nanowire form offer high theoretical capacities for batteries. Their nanostructured forms mitigate issues like poor conductivity and large volume expansion. For instance, TiO₂ nanowires provide a stable structure for lithium-ion insertion/extraction, ensuring long cycle life.

3. Silicon and Alloy Nanostructures for Anodes

Silicon has a theoretical capacity nearly ten times higher than conventional graphite anodes but suffers from massive volume expansion (>300%). Nanostructuring silicon into nanoparticles, nanowires, or porous networks can accommodate this expansion, preventing electrode pulverization and capacity fade.

4. Nanostructured Sulfur Composites for Li-S Batteries

Lithium-sulfur batteries promise high energy density but are plagued by polysulfide dissolution. Confining sulfur within nanostructured carbon hosts or using sulfide nanomaterials can trap polysulfides, enhancing cycle stability.

Performance Comparison of Nanostructured Electrode Materials

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of selected nanostructured materials compared to traditional materials in energy storage.

| Material Type | Specific Surface Area (m²/g) | Typical Capacity (mAh/g or F/g) | Cycle Life (Cycles) | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphite (Bulk) | 5-20 | ~372 mAh/g | >1000 | Li-ion Battery Anode |

| Silicon Nanowires | 50-200 | >2000 mAh/g | 500-1000 | High-Capacity Anode |

| Activated Carbon (Bulk) | 1000-2000 | ~100 F/g | >50,000 | Supercapacitor |

| Graphene Foam | ~2600 | 150-200 F/g | >100,000 | Supercapacitor |

| LiCoO₂ (Bulk Cathode) | <1 | ~140 mAh/g | 500-800 | Li-ion Battery Cathode |

| LiFePO₄ Nanoparticles | 20-50 | ~170 mAh/g | >2000 | Li-ion Battery Cathode |

Synthesis and Manufacturing Challenges

While lab-scale synthesis of nanomaterials (e.g., chemical vapor deposition, sol-gel processes) is well-established, scaling up production remains a significant hurdle. Challenges include maintaining consistent nanostructure, controlling defects, managing high costs, and ensuring environmental safety. Furthermore, integrating nanomaterials into practical devices requires careful electrode design and electrolyte compatibility.

Future Perspectives and Conclusion

The future of nanostructured materials in energy storage lies in the development of multifunctional, hybrid architectures. Examples include graphene-metal oxide composites, 3D-printed nano-architected electrodes, and bio-inspired nanostructures. Research is also focusing on sustainable and low-cost synthesis routes. As understanding of nano-ionic phenomena deepens, these materials will play a pivotal role in enabling next-generation technologies like solid-state batteries, fast-charging systems, and grid-scale storage, ultimately accelerating the transition to a renewable energy economy.

In summary, nanostructured materials provide a powerful toolkit to overcome the intrinsic limitations of current energy storage materials. By continuing to innovate in material design, synthesis, and integration, we can unlock unprecedented performance, bringing us closer to a future of reliable, high-density, and rapid energy storage solutions.