Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage: Principles and Applications

Note:

In the global pursuit of sustainable energy solutions and enhanced energy efficiency, Thermal Energy Storage (TES) has emerged as a critical technology. Among various TES methods, the use of Phase Change Materials (PCMs) stands out due to their ability to store and release large amounts of thermal energy during phase transitions, typically from solid to liquid and vice versa. This article delves into the science behind PCMs, their classifications, key applications, and the future trajectory of this promising technology.

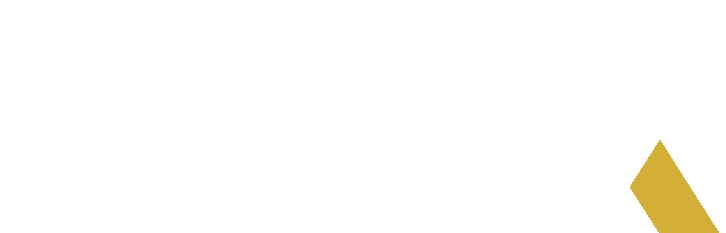

1. The Fundamental Working Principle of PCMs

Phase Change Materials operate on a simple yet powerful principle: they absorb, store, and release thermal energy during the process of changing their physical state. When the temperature around a PCM rises to its melting point, it absorbs a significant amount of heat (known as latent heat) and changes from solid to liquid. This process occurs at a nearly constant temperature. Conversely, when the ambient temperature falls below the material's freezing point, the PCM solidifies, releasing the stored latent heat back into the environment.

Figure 1: Latent heat storage process during phase transition of a PCM.

This isothermal nature of energy storage is a key advantage over sensible heat storage (like heating water), where temperature changes continuously. The high energy density of latent heat storage allows for much more compact thermal storage systems.

2. Classification and Types of Phase Change Materials

PCMs are broadly categorized based on their chemical composition and phase transition temperature. The selection of a PCM depends heavily on the application's required temperature range.

2.1 Organic PCMs

These include paraffin waxes and non-paraffin compounds like fatty acids. They are known for their chemical stability, non-corrosiveness, and congruent melting (melting and freezing without phase segregation). However, they often have low thermal conductivity and can be flammable.

2.2 Inorganic PCMs

This category encompasses salt hydrates, metallic alloys, and salts. Salt hydrates, like sodium sulfate decahydrate, are very common due to their high volumetric latent heat storage capacity and high thermal conductivity. A drawback can be supercooling, where the material does not solidify at its freezing point.

2.3 Eutectic Mixtures

Eutectics are mixtures of two or more components that melt and freeze congruently at a specific temperature, forming a mixture of crystals. They can be organic-organic, inorganic-inorganic, or organic-inorganic blends, offering tailored phase change temperatures.

| PCM Type | Examples | Phase Change Temp. Range | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic (Paraffin) | Octadecane, Paraffin Wax | ~5°C to 80°C | Chemically stable, non-corrosive, no supercooling | Low thermal conductivity, flammable |

| Inorganic (Salt Hydrate) | Sodium Sulfate Decahydrate, Calcium Chloride Hexahydrate | ~5°C to 130°C | High latent heat, high thermal conductivity, non-flammable | Can suffer from supercooling and phase segregation |

| Fatty Acids | Capric Acid, Lauric Acid | ~0°C to 80°C | Good thermal reliability, reproducible melting/freezing | Costly, lower latent heat than salts |

| Eutectic (Organic-Organic) | Capric-Lauric Acid mixture | Adjustable (e.g., ~20°C) | Sharp melting point, customizable properties | Complex formulation, limited data available |

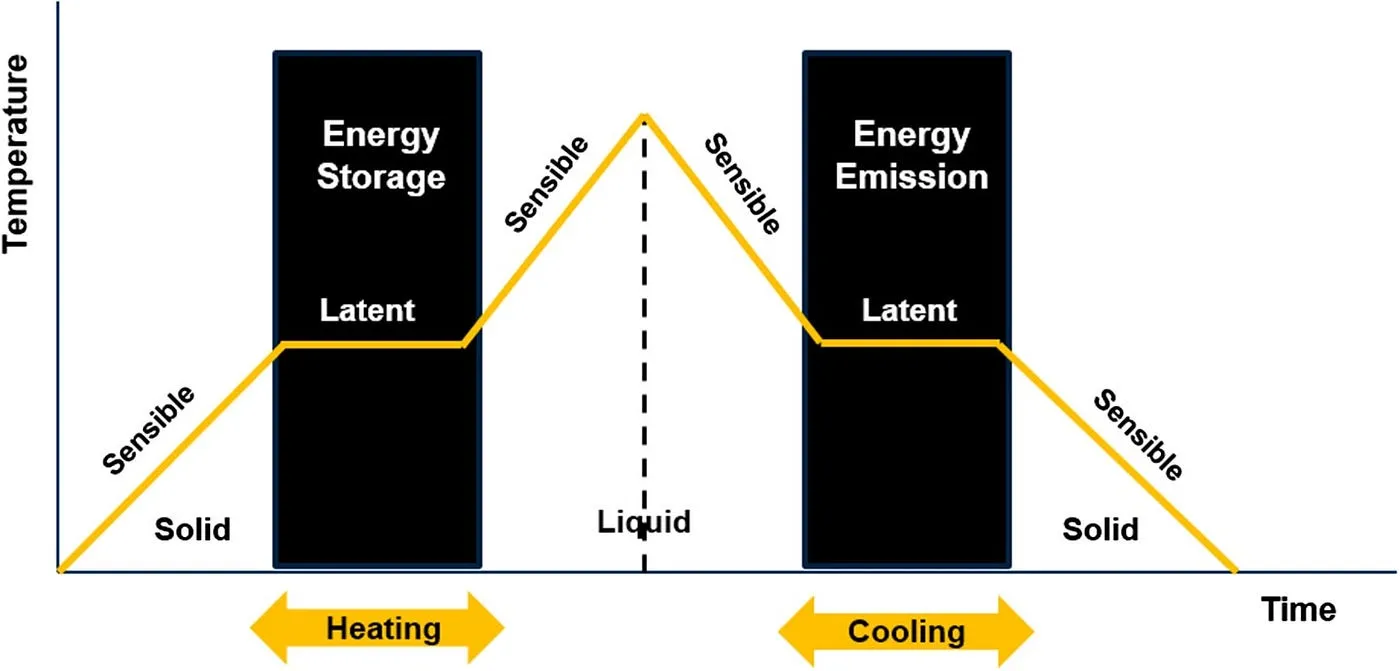

Figure 2: Visual comparison of different types of PCMs.

3. Key Application Areas of PCMs

3.1 Building and Construction

Integrating PCMs into building materials (gypsum boards, concrete, plaster) is a major application. They help in passive thermal management, reducing heating and cooling loads by absorbing excess heat during the day and releasing it at night. This significantly enhances building energy efficiency and occupant comfort.

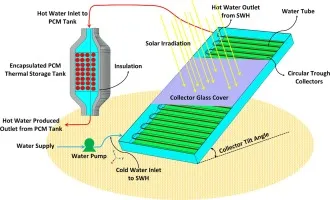

3.2 Solar Thermal Energy Systems

PCMs address the intermittency of solar energy. They store excess thermal energy collected by solar thermal panels during sunny periods and release it when sunlight is unavailable (at night or on cloudy days), enabling more consistent hot water supply or space heating.

Figure 3: Integration of PCM storage in a solar thermal system.

3.3 Thermal Management of Electronics

High-power electronics generate significant heat. PCMs are used in heat sinks and casings to absorb transient thermal loads, preventing overheating and improving device reliability and lifespan, especially in portable electronics and LED systems.

3.4 Textiles and Clothing

Microencapsulated PCMs are embedded in fabrics for smart clothing. They provide thermal buffering, keeping the wearer comfortable in varying temperatures by absorbing excess body heat and releasing it when needed.

4. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite their potential, PCMs face challenges that drive current research. Key issues include enhancing low thermal conductivity (often solved by adding conductive fillers like graphite or metal foams), ensuring long-term stability over thousands of cycles, preventing leakage (solved by encapsulation or shape-stabilization), and reducing costs for large-scale deployment.

The future of PCMs lies in the development of novel composite and nano-enhanced materials, bio-based sustainable PCMs, and advanced macro/micro-encapsulation techniques. Integration with smart grids and IoT for active energy management in buildings is also a promising direction. As material science advances, PCMs are poised to play an indispensable role in the global transition to a more efficient and renewable-based energy infrastructure.

| Application Sector | Typical PCM Type Used | Required Temperature Range | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building Comfort | Paraffin, Salt Hydrates | 18°C - 28°C | Peak load shifting, temperature regulation |

| Solar Water Heating | Salt Hydrates, Paraffin | 45°C - 80°C | Bridging supply-demand mismatch |

| Electronic Cooling | Paraffin, Eutectics | 40°C - 80°C | Passive thermal buffering |

| Cold Chain & Food Storage | Water-based solutions, Salt Hydrates | -20°C to 5°C | Maintaining low temperatures |