Superconductor Materials: Revolutionizing Modern Technology

Superconductors represent one of the most fascinating and technologically promising classes of materials discovered in the 20th century. These extraordinary materials exhibit zero electrical resistance and perfect diamagnetism when cooled below a critical temperature, enabling current to flow indefinitely without energy loss. The study and development of superconducting materials have opened up revolutionary possibilities across numerous fields including energy transmission, medical imaging, transportation, and quantum computing.

Fundamental Principles of Superconductivity

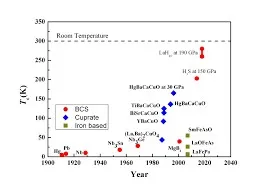

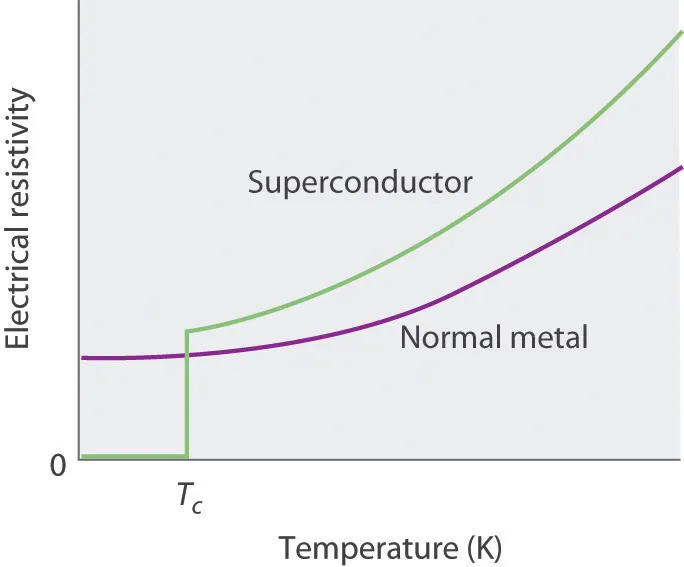

Superconductivity was first discovered in 1911 by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes when he observed that mercury lost all electrical resistance at temperatures near absolute zero. This phenomenon occurs when electrons form Cooper pairs through interactions with the crystal lattice, allowing them to move without scattering. The transition to the superconducting state is characterized by two key properties: zero electrical resistance and the Meissner effect, where magnetic fields are expelled from the material's interior.

The critical temperature (Tc), critical magnetic field (Hc), and critical current density (Jc) define the operational limits of any superconductor. Understanding these parameters is essential for practical applications, as they determine the conditions under which superconducting properties can be maintained.

Classification of Superconducting Materials

Superconductors are broadly categorized based on their critical temperature and fundamental properties:

Type I Superconductors

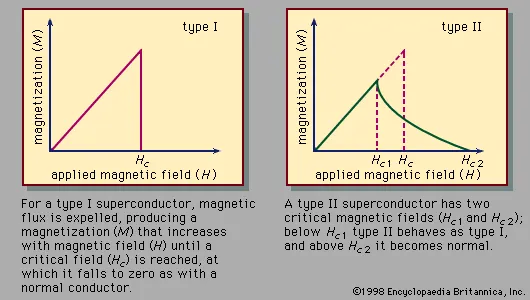

These are typically pure elemental metals that exhibit perfect diamagnetism and transition abruptly to the normal state when exposed to magnetic fields exceeding their critical value. Type I superconductors generally have low critical temperatures (below 10K) and find limited practical applications due to their low field tolerance.

Type II Superconductors

These materials, including most high-temperature superconductors and metallic compounds, allow magnetic flux to penetrate in quantized vortices while maintaining superconductivity in the remaining material. This property enables them to withstand much higher magnetic fields, making them suitable for most practical applications.

Major Superconductor Material Families

Elemental Superconductors

Several pure elements exhibit superconducting properties at low temperatures. Niobium has the highest critical temperature (9.2K) among elemental superconductors, followed by technetium (7.8K), lead (7.2K), and vanadium (5.4K). These materials are primarily used in fundamental research and specialized applications.

Low-Temperature Superconductors (LTS)

These materials require liquid helium cooling (4.2K) to maintain superconducting states. The most technologically important LTS materials include:

| Material | Critical Temperature (K) | Critical Field (T) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NbTi | 9.8 | 15 | MRI magnets, particle accelerators |

| Nb₃Sn | 18.3 | 30 | High-field magnets, fusion devices |

| PbMo₆S₈ | 15.2 | 60 | Very high-field applications |

Niobium-titanium (NbTi) alloys dominate commercial superconductor markets due to their excellent mechanical properties and relatively straightforward manufacturing process.

High-Temperature Superconductors (HTS)

The discovery of high-temperature superconductors in 1986 revolutionized the field by demonstrating superconductivity at temperatures achievable with liquid nitrogen (77K). Major HTS families include:

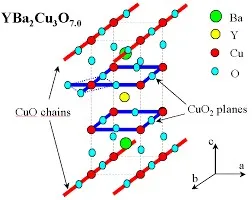

Cuprate Superconductors

These copper-oxide based materials were the first high-temperature superconductors discovered. Notable examples include YBCO (YBa₂Cu₃O₇, Tc=92K) and BSCCO (Bi₂Sr₂Ca₂Cu₃O₁₀, Tc=110K). Their anisotropic layered structure presents manufacturing challenges but enables exceptional current-carrying capabilities.

Iron-Based Superconductors

Discovered in 2008, these materials contain iron layers and exhibit critical temperatures up to 55K. Unlike cuprates, they demonstrate more isotropic properties and higher upper critical fields, making them promising for high-field applications.

MgB₂ Superconductor

Magnesium diboride (MgB₂), discovered in 2001, bridges the gap between LTS and HTS with a critical temperature of 39K. Its simple crystal structure, low material costs, and high critical current density make it attractive for various applications.

Recent Developments in Superconductor Materials

Hydride-Based Superconductors

Recent research has demonstrated superconductivity at near-room temperatures in hydrogen-rich materials under extreme pressures. Lanthanum decahydride (LaH₁₀) has shown superconductivity up to 250K, though requiring pressures exceeding 150 GPa. These discoveries provide crucial insights into the mechanisms of high-temperature superconductivity.

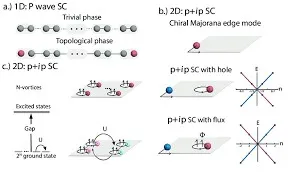

Topological Superconductors

This emerging class of materials hosts Majorana fermions at their boundaries, which are theorized to be building blocks for fault-tolerant quantum computing. Materials such as FeTe₀.₅₅Se₀.₄₅ and engineered heterostructures show promise in this rapidly developing field.

Applications of Superconducting Materials

The unique properties of superconductors have enabled transformative technologies across multiple sectors:

Medical Imaging

Superconducting magnets form the core of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) systems, providing the stable, high magnetic fields necessary for high-resolution medical diagnostics. NbTi wires are predominantly used in these applications due to their reliability and performance at liquid helium temperatures.

Energy and Power Systems

Superconducting cables can transmit electricity with minimal losses, potentially revolutionizing power grids. Fault current limiters based on superconductors provide rapid protection for electrical networks. Emerging applications include superconducting generators for wind turbines and energy storage systems.

Scientific Research

Large-scale scientific facilities such as particle accelerators (LHC at CERN) and nuclear fusion reactors (ITER) rely on superconducting magnets to generate intense magnetic fields necessary for their operation. These applications typically utilize Nb₃Sn or HTS materials for their superior high-field performance.

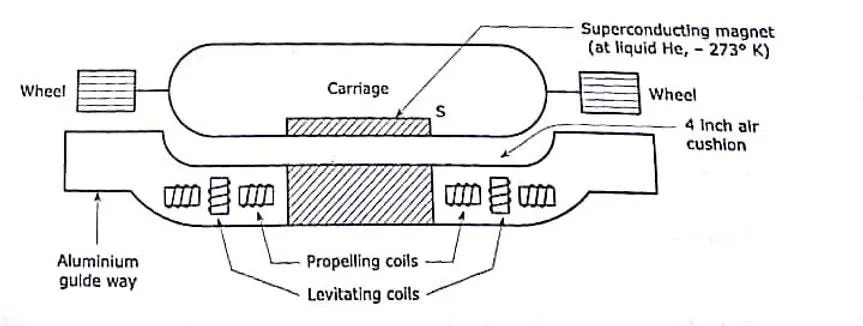

Transportation

Maglev trains employing superconducting magnets enable frictionless travel at high speeds. Development continues on superconducting motors for electric aircraft and ships, offering significant weight and efficiency advantages over conventional technologies.

Quantum Computing

Superconducting qubits, typically fabricated from aluminum or niobium circuits, represent the leading platform for developing practical quantum computers. The coherent quantum states in these circuits enable complex quantum operations essential for quantum information processing.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, widespread adoption of superconducting technologies faces several challenges:

| Challenge | Current Status | Research Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Cooling Requirements |

LTS: Liquid helium (4K)

HTS: Liquid nitrogen (77K) |

Room-temperature superconductors |

| Material Costs | HTS materials remain expensive | Alternative compositions, manufacturing optimization |

| Mechanical Properties | HTS materials are brittle | Composite structures, flexible conductors |

| Current Anisotropy | Cuprates have directional current flow | Grain boundary engineering, isotropic materials |

Future research focuses on discovering new superconducting materials with higher critical temperatures, developing practical room-temperature superconductors, improving manufacturing processes to reduce costs, and enhancing the mechanical properties of HTS wires for demanding applications.

Conclusion

The field of superconductor materials continues to evolve rapidly, with ongoing discoveries expanding our understanding of fundamental physics while enabling transformative technologies. From the elemental superconductors of the early 20th century to the complex high-temperature compounds of today, these remarkable materials have consistently pushed the boundaries of what is physically possible. As research advances toward the holy grail of room-temperature superconductivity, we can anticipate even more dramatic impacts on energy, transportation, computing, and medicine in the coming decades.