What is Biodegradable Material? A Comprehensive Guide

In an era increasingly defined by environmental consciousness, the term "biodegradable material" has become a cornerstone of sustainable discourse. But what does it truly mean? At its core, a biodegradable material is a substance that can be broken down naturally by microorganisms—such as bacteria, fungi, and algae—into water, carbon dioxide (or methane), and biomass. This process, known as biodegradation, is nature's way of recycling organic waste, and it stands in stark contrast to the persistence of conventional plastics and synthetics that clog landfills and pollute ecosystems for centuries.

The Science Behind Biodegradation

Biodegradation is a complex biochemical process. Microorganisms secrete enzymes that break down complex organic polymers into simpler compounds, which they then absorb as nutrients. The rate and completeness of this process depend on several critical factors:

Key Factors Affecting Biodegradation:

- Material Composition: The chemical structure of the material itself (e.g., plant-based cellulose vs. synthetic polyester).

- Environmental Conditions: Presence of oxygen (aerobic vs. anaerobic), temperature, moisture, and pH levels.

- Microbial Population: The type and quantity of microorganisms present in the environment.

It is crucial to distinguish between materials that are inherently biodegradable (like food scraps, paper, cotton) and those engineered to be industrially compostable. The latter often requires specific, managed conditions found in commercial composting facilities to break down efficiently.

Types and Examples of Biodegradable Materials

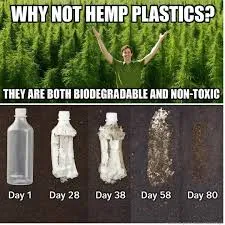

Biodegradable materials span a wide spectrum, from naturally occurring substances to innovative bioplastics.

1. Natural Biodegradables

These are materials derived directly from nature with no synthetic modification.

- Plant-based: Wood, cotton, hemp, bamboo, cork, straw.

- Animal-based: Wool, silk, leather, bone.

- Food Waste: Vegetable peels, eggshells, coffee grounds.

2. Engineered Bioplastics and Biopolymers

This category includes materials designed to mimic the functionality of conventional plastics but with the ability to biodegrade under the right conditions.

| Material Type | Raw Material Source | Common Applications | Typical Decomposition Time* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Corn starch, sugarcane | Food packaging, disposable cutlery, 3D printing filament | 3-6 months (industrial compost) |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) | Microbial fermentation of sugars/lipids | Medical implants, biodegradable coatings, packaging films | 3-12 months (soil/marine) |

| Starch Blends | Potato, corn, or tapioca starch | Loose-fill packaging "peanuts", shopping bags | 2-5 months (compost) |

| Cellulose-based Films | Wood pulp, cotton | Transparent packaging, food wrappers | 1-3 months (compost) |

*Decomposition times are approximate and highly dependent on specific environmental conditions.

Benefits and Challenges of Biodegradable Materials

Significant Benefits

The advantages of adopting biodegradable materials are multifaceted and compelling:

- Waste Reduction: They divert waste from overflowing landfills, reducing the volume of long-term garbage.

- Lower Carbon Footprint: Often derived from renewable resources, their production and breakdown typically generate fewer greenhouse gases compared to petroleum-based plastics.

- Ecosystem Safety: They break down into non-toxic components, minimizing soil and water pollution and reducing the threat to wildlife from ingestion or entanglement.

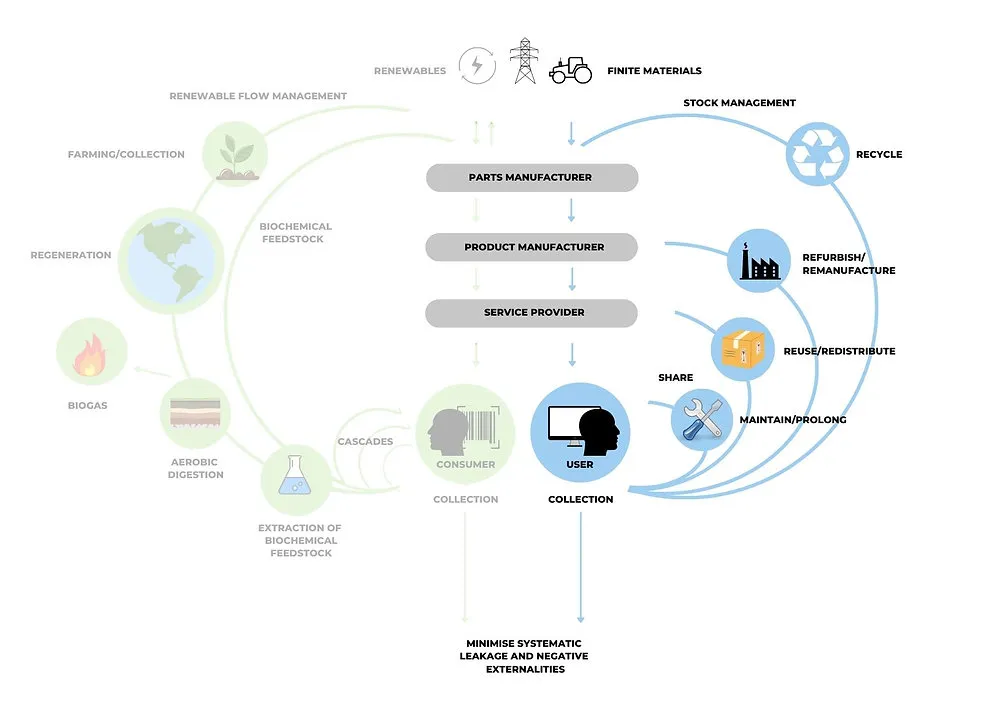

- Circular Economy Support: They can be integrated into composting systems, returning valuable nutrients to the soil and closing the biological loop.

Critical Challenges and Considerations

Despite their promise, biodegradable materials are not a perfect, one-size-fits-all solution.

- Conditional Breakdown: Many require specific industrial composting facilities (with high heat and humidity) to degrade efficiently. In a home compost or landfill, they may break down very slowly or not at all.

- Potential for Contamination: If mixed with conventional plastics in recycling streams, they can compromise the quality and recyclability of the entire batch.

- Resource Use: Growing crops for bioplastics can compete with food production for land, water, and fertilizers.

- Consumer Confusion: Terms like "biodegradable," "compostable," and "bio-based" are often used interchangeably, leading to improper disposal and "greenwashing" concerns.

The Future: Innovation and Responsible Use

The future of biodegradable materials lies in continued innovation and systemic integration. Researchers are developing next-generation materials that degrade faster in diverse environments, including marine settings. Policy frameworks and standardized labeling (like certifications from the Biodegradable Products Institute - BPI) are crucial to guide proper use and disposal. Ultimately, biodegradable materials are a powerful tool within a broader sustainability strategy that prioritizes reduction, reuse, and recycling first.

In conclusion, biodegradable materials represent a critical step towards harmonizing human consumption with planetary cycles. By understanding their nature, proper applications, and limitations, we can make informed choices that genuinely contribute to a less polluted and more sustainable world.